Emerald Ash Borer topic of session for black ash weavers, pounders

By Ken Luchterhand

An informational session about the devastation being caused by the Emerald Ash Borer to the black ash trees in Wisconsin was held on October 28 at Ho-Chunk Gaming – Black River Falls conference room.

“We held the meeting because the Emerald Ash Borer was found in Jackson County in August, which made formulating a response all the more urgent,” said HCN Forester Mark Gawron. “Also, the addition of Greg Blick to the DNR staff, who has experience formulating EAB response plans for municipalities in Illinois and Missouri, gave the DNR enough resources to plan the meeting. Furthermore, Kjetil Garvin finished her survey of basket trees on tribal lands this summer and we were able to use those results to inform our planning. She found only 14 trees suitable for basket making in her survey.”

The consensus reached by the pounders and weavers was that the first priority should be harvesting as many good basket trees as possible before they are destroyed by the bug, pound them out immediately, and store the resulting splints for the long term, Gawron said.

Second priority is collecting black ash seed and starting a plantation which will provide a source of black ash to future generations. It is hoped in the future resistant strains of black ash will be found that can survive EAB. Otherwise, this plantation may have to be grown in a modified greenhouse or under netting. This latter idea of netting was an idea thought up by Ho-Chunk basket makers during the meeting, and if we did pursue it we would be breaking new ground, Gawron said.

One of the main speakers for the event was Kelly Church, who is a fifth generation award-winning basket maker. She grew up in southwest Lower Michigan, an enrolled member of the Grand Traverse band of the Ottawa Chippewa Indians. She’s a woodlands style painter, a birch bark biter and an educator.

The Emerald Ash Borer was discovered in Michigan in 2002.

“When they found the destruction cause by the Emerald Ash Borer, they found out that it actually had been in the state for 10 years and it took that long to discover its presence. What I like to tell people is: You just discovered it in Wisconsin in 2013. Most likely it was here years before that. That is just when you discovered the bug. That doesn’t mean when it arrived here,” she said. “It’s here in more places than you discovered.”

The Emerald Ash Borer was discovered in Pennsylvania in 2007, but it was in the state six years before that when checking the growth rings of the tree and the damage incurred, she said.

She considers herself a product of an unbroken family line of basket weavers. In Michigan, there are 40 basket weavers, of which 25 are from her family.

She remembers when families would get together to harvest a tree. They didn’t have any black ash on the reservation, so they had to rely on private landowners to allow them to harvest.

Within the tribe, many black ash seeds have been collected for future planting projects. The Saginaw Chippewa tribe has collected a lot of seeds in 2006, she said. Another tribe, Pokagon, has been doing experiments on the black ash trees by inoculating the trees yearly for the last three years. Although the trees have been thriving, upon closer inspection, the leaves are really dark green bordering on brown.

“Maybe too much injection,” she said. “What has been recommended is once every two or three years. You have the think about it going into the soil and being absorbed by seedlings, then the deer eat the seedling and we eat the deer.”

As far as the present situation, the best they can do is use what is available to them.

“We don’t have access to black ash in the Lower Peninsula anymore. In March 2014 was the last time we harvested a black ash tree. It was a beautiful tree, 40 to 50 feet high, but it was galleried from top to bottom,” she said.

When they would harvest a tree with EAB damage, they would use a shave knife to remove all the outer layers to get to undamaged part and then begin pounding. It would result in wasting all the green wood, but the damaged material needed to be removed, she said.

“Used to be, I could go 15 minutes in any direction to harvest a tree, but they are all gone now in the Lower Peninsula.

“I can go to any of the stands of black ash and not find any live trees,” she said. “But we are seeing some of the seedlings survive.”

In 2011 and 2012, the tribe collected as many seeds as possible. They collected by using pruning poles and shaking the trees. After gathering them, the seeds would be placed in paper bags to dry, then stored in the freezer. If stored properly, they can remain good for 25 to 30 years, but not all seeds will be viable.

“Out of 100 seeds, you might only have 10 that are good,” she said. “Try to get all the seeds you can from a tree before harvesting it. I knew where a nice tree was, but it was producing seeds, so we left it. The next year it was dead.

“It can go quicker than you can imagine,” Church said. “Black ash will only seed every five to seven years and the Emerald Ash Borer can kill in three to five years, so you have to concentrate on those seeds. Seeds is the number one thing we have to think about.”

She thought that, if the EAB was going to start anywhere in the United States, that lower Michigan would be the best place because it is isolated, being bordered on three sides by the Great Lakes. But, unfortunately, it was removed from the state because people moved firewood, plus a nursery sent tree stock to Virginia.

“This year we are harvesting black ash in the Upper Peninsula, which is a whole different environment,” she said. “The UP is a drier climate. The wetter areas have better black ash. To harvest the trees and to split them – it’s just not the same. The logs are much drier in the UP.”

They try to get the youth involved in the harvesting as much as possible. For instance, they harvested a tree next to a stream that had an abundance of fish. The youth wanted to go fishing.

“If you get the pounding done first,” Church said. “That gave them a little incentive to get going on the project and make the whole project an enjoyable experience.”

One of the most important things that youth need to experience is how to collect seeds, teach them about the tree and how it looks, and teach them everything you know because they are the ones that will carry on the knowledge.

“They’re the ones, in 40 to 50 years, who will be teaching other people,” she said.

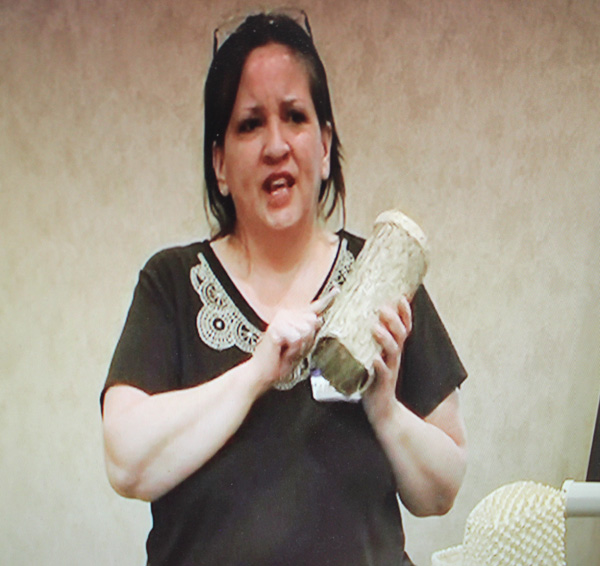

Church showed a cylindrical craft she referred to as a “bark basket.” She said she doesn’t sell them regularly anymore, but keeps them as educational material to show what black ash bark looks like.

She also has made a number of flash cards with photos as identifiers of black ash. She will use them during her educational sessions. The photos show the bark, the leaves, buds and various aspects and stages of the black ash.

“The only tree that you could possibly get the bark mixed up with is elm, but the leaves are different,” she said.

Church has a positive outlook about the survival of black ash. In China, ash has developed a resistance to the EAB and she thinks the black ash also will do so in the United States.

“I think our trees, in the next decade, could also gain a resistance. But that may be wishful thinking,” she said. “There are elm trees out there, which are pretty big. We thought we would lose all our elm but there are some still around and growing.”

She said 99 percent of the black ash trees in lower Michigan, 503 million, are dead, but she is hopeful the one percent will continue to grow and survive.

“This bug is moving fast, is hardier than we thought. It’s good for us to act quickly as well,” Church said.

In China, they released a certain type of wasp that kills the EAB and has a 70 percent effective rate. That might work in the U.S., but it would involve introducing an invasive species, which could have adverse long-term effects.

“I like to say let’s count on our own native species,” she said. “For instance, woodpeckers eat 15 to 16 percent of the EAB, but they also destroy the bark. There are three or four other wasps that might control the Emerald Ash Borer that is native to our area.”

In the meanwhile, she is preparing for the worst by creating all types of educational material for future generations, such as pictures and videos that show the various stages of harvesting, pounding, stripping and weaving of baskets.

“We’re probably going to miss a generation of harvesters and weavers due to the Emerald Ash Borer,” Church said.

Her fulltime job is making baskets and educating people how to harvest, pound, strip and weave.

“I make a living from baskets,” she said.

Pounders are one of the most important people in developing the trade and they are becoming fewer.

“I have a husband who pounds and that’s like their assurance we’ll never divorce them if you’re a basket weaver,” she said. “I don’t know if I could ever find another pounder. So my husband always thinks he has it made.”

In the Traverse Bay Band, if young men get into trouble with the law, for probation they have to go to a weaver’s house to pound. It’s not a punishment. It’s getting them back into their culture, she said. After probation, the weaver will pay them to pound, so it is a way for them to make money.

Also, if black ash becomes extinct, there are other materials that can be used. For instance, cattails, bulrushes and cedar can be weaved into mats and baskets can be made from birch bark.

“We can use many materials and skills that haven’t been used for a while – skills that have been lost,” she said.

Home